Thierry Guetta’s (Aka Mr Brainwash) Version Of Glen Friedman’s Photograph Of Run Dmc

Thierry Guetta’s (Aka Mr Brainwash) Version Of Glen Friedman’s Photograph Of Run Dmc

COPYRIGHT COPYCAT

In our current era of fast-forward information exchange, instant publishing, super-speed blogging and instant screen grabs, intellectual property protection has become as precious as diamonds. These days with a few clicks of the mouse all the original ideas of the most famous artists and creatives around the globe are available at your disposal and protecting good ideas has become close to impossible.

There has been a dramatic rise over the past few years of copyright infringement cases – in particular since the internet explosion of websites and blogs facilitated access to the masses of the latest designer collections straight off the runway, creative industry portfolios and digital music downloads. The limits of creativity in contemporary culture have been challenged on numerous occasions in the past six months as both fashion and art industries have racked up multiple copyright infringement cases that have made the headlines internationally.

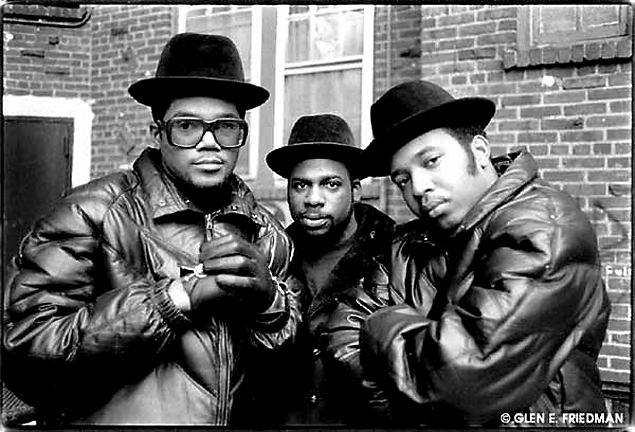

In March photographer Glen Friedman filed a suit against street-artist Thierry Guetta, AKA Mr. Brainwash, over an image of rap group Run DMC. According to Friedman, Guetta reproduced his well-known 1985 photograph without permission and used graffiti-art clones to produce artwork, promotional pieces and prints for his debut public exhibition, “Life is Beautiful.” Guetta in fact downloaded off the internet the iconic image of Run DMC, considered to be one of the most famous images ever produced of the band. He projected it onto a piece of wood and painted the image as well as glued 1,000 pieces of vinyl records to the piece, although the image itself remained clearly recognizable. He also did several other renditions of the image as limited edition screen prints.

RUN DMC PHOTOGRAPH BY GLEN FRIEDMAN, 1985

RUN DMC PHOTOGRAPH BY GLEN FRIEDMAN, 1985

Friedman’s lawyer, Douglas Linde demanded a percentage of the indirect profits from Guetta’s exhibition as compensation for his infringement based on the terms that, in copying Friedman’s image, Guetta diverted trade away from his business and diluted the value of its rights and that he was a “blatant plagiarist.” It was alleged that Guetta profited from the artworks and that the image was distributed in acts of “widespread self-promotion”. In response to such claims, Guetta claimed his actions were protected by fair-use laws and freedom of speech.

The California federal judge Dean Pregerson dismissed Geutta’s argument, ruling that transformative fair use law was not a legitimate defense in the case. “To permit one artist the right to use without consequence the original creative and copyrighted work of another artist simply because that artist wished to create an alternative work would eviscerate any protection by the copyright act,” said Judge Pregerson in his ruling. “Without such protection, artists would lack the ability to control the reproduction and public display of their work and, by extension, to justly benefit from their original creative work.” The decision will most certainly impact the art world, as it will limit artists the ability to freely use manipulated images in art, which has previously been successfully defended with the transformative fair use law.

The case also flags up warning signs to the street-art industry’s common use of iconic imagery, which has remained a fairly under-cover practice. This under-ground status has been lifted in recent years as street-artists, such as Alec Monopoly and Thierry Guetta, led by the likes of Banksy, have started exhibiting their work formally. This shift, along with an increased price tag on their works, has changed the status of both their work and their roles as artists. Many street artists have been pre-disposed to use popular images in their artwork, like the Monopoly man, which, when brought into the context of formal exhibitions, extinguishes the artist’s previous anonymity and, with the added effect of a hefty price-tag, opens their practice up to previously unregistered copyright accusations.

PHOTOGRAPH BY JANINE GORDON

PHOTOGRAPH BY JANINE GORDON

Photographer Janine Gordon has not been as fortunate with her copyright infringement accusations against fellow fine art photographer Ryan McGinley. Gordon accused McGinley of copying over 150 of her photographs over the course of six years, notably for various commercial campaigns including Levi’s. From the onset of hearing such an accusation it seems that either McGinley is some form of creative stalker, with no creative originality to his name, or that Gordon deems herself the only photographer able to photograph certain poses. However, on taking a closer look at the ‘evidence’ for the case, one can certainly determine similarities in some of their photographs and understand, to an extent, why Gordon has brought the case to court. Both artists have exhibited at the same museums and galleries over the years, including the Whitney Museum of American Art, Schirn Kunsthalle Gallery, Ratio 3 Gallery in San Francisco, Peter Hay Halpert Fine Arts and Team Gallery. Gordon claimed McGinley’s proximity to Gordon’s work “during the preparation and display of the Whitney exhibition in which he participated,” gave him “total and complete access to view and examine the Gordon images featured in the 2002 Whitney Biennial.” According to the 10 page document, McGinley was accused of copying Gordon’s ‘original’ signature style. As her supporter, Julio Mitchel, Gordon’s former photography teacher at The Cooper Union School of Art, asserted, ‘it is true that one artist’s work can overlap in idea or style with another, but I have rarely seen, as I do here, such a consistent overlap of a series of works created by one artist over years with the works of another […] I can identify an obvious and latent similarity parties’ works as well as in their themes and energy. Changing the direction of a head, a background setting, or a slight color shift, does not constitute a new vision where the lighting, content and composition are the same.” Former New Museum curator Dan Cameron supported Gordon’s case in an affidavit. “My long-term expertise as a critic and curator gives me, I believe, sufficient authority to say, without hesitation, that Ms. Gordon’s work is completely original, in concept, color, composition and content, and that Ryan McGinley has derived much of his work from her creations,” he writes.

Despite such support from art world authorities and having works in the permanent collections of the Whitney, SFMOMA amongst numerous other museum and gallery exhibits internationally, Judge Sullivan deemed the case ‘not a serious dispute’ adding, ‘’you know you can go to the MOMA and have this conversation […] I really do think this is as basic as it gets and I don’t think this is copyrightable.’ Quite ironically, the Judge relied heavily upon Gordon’s own visual evidence in dismissing the case, ‘the Plaintiff’s apparent theory of infringement would assert copyright interests in virtually any figure with outstretched arms, an interracial kiss, or any nude female torso’s.’ Gordon’s case did in fact take the infringement accusation deeper than simple compositional copy. Unfortunately for creative people within the realms of fashion and art, copyright laws do not protect ‘ideas, principles or explanations.’

The case is currently under appeal, which was due to be heard on December 2nd, although Gordon petitioned the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit for a 60-day extension because of the holidays and so she has time to “educate myself in the law,” as she will be defending herself. McGinley, as well as co-defendants Levi’s, Team Gallery and Ratio 3 Gallery, are cross-appealing for legal expenses, asking for $106,000 which is “substantially less than the actual fees incurred.” They offered to forgo suing Gordon for legal expenses if she agreed not to appeal. Gordon has refused to consider canceling her appeal stating, “I will take this to the bitter end with them.” It is clear that she feels her style and works have been exploited by the obvious similarities in his work and campaign imagery, particularly in subject matter, composition, stylistic direction and lighting, and that he is profiting grossly off of her ideas. “This is an art world travesty, when artists can freely steal from another artist for 10 years and be praised, paid and dance in the sun all day,” Gordon said in an email to Artnet News, adding that her prints go for $5,000 while those of her younger, more successful counterpart might go for more than $20,000. “They eat lobster and drink champagne and I eat beans and soup for dinner.”

SHOES BY CHRISTIAN LOUBOUTIN

SHOES BY CHRISTIAN LOUBOUTIN

On the fashion front, the case of Christian Louboutin vs Yves Saint Laurent made massive headlines after Louboutin sued YSL for copying his signature red-soled high heels.After seeing red-soled platforms in YSL’s summer cruise line collection, Louboutin swiftly elicited a hefty lawsuit which barred sale of the shoe. YSL’s lawyer defended his client stating ‘no designer should be able to monopolize a primary color for fashion.’

The Louboutin trademark, obtained in 2008, which consists of a lacquered red sole on footwear, notes that the color red is a feature of the mark. Despite that the presiding judge, U.S. District Judge Victor Marrero, decided that maybe Louboutin’s trademark wasn’t even valid and that the case was dismissible as one designer shouldn’t be able to have a “monopoly” on a color. “Awarding one participant in the designer shoe market a monopoly on the color red would impermissibly hinder competition among other participants,” Marrero wrote. “Louboutin’s ownership claim to a red sole would harm competition not only in high fashion shoes, but potentially in the markets for other fashion articles as well, putting makers of dresses, coats, bags, hats and gloves in fear of lawsuits.” The judge said the trademark was unlikely to survive legal challenges “because in the fashion industry color serves ornamental and aesthetic functions vital to robust competition.”

Louboutin is currently appealing the decision, with his counsel’s argument emphasizing that “the red sole is too vital to the brand’s identity and allowing other companies to use it would be harmful to the company.” The latest appeal reiterates Louboutin’s initial argument and takes it a bit further, accusing the judge of making “errors of law in determining that Louboutin’s red outsole mark was likely invalid.” The case itself put Louboutin in danger of losing his trademark on red soles, leaving the floodgates open for any shoe company to put red soles on their designs, and thus completely destroy his brand identity. Other companies, notably Tiffany and Co, could also be in danger of their trademarks being invalidated, as they include particular colors as part of their signature.

The fight remains to be resolved in these latter cases, and in many respects all of them represent challenges in the legal battle to protect intellectual property. The battle is just beginning, as information exchange evolves, it will become harder and harder to protect against our current copycat culture of plagiarism and piracy.

Article by Indira Cesarine, assisted by Emma Corbett